The Private AI Series, Course 1, Part 1

Society runs on information flows: My summary of lesson 1 & 2 of the first course in The Private AI Series by OpenMined

- I started taking The Private AI Series by OpenMined

- Society Runs on Information Flows

- Information Flow

- What Does Privacy Mean?

- Data is Fire 🔥

- Privacy and Transparency Dilemmas

- The Privacy-Transparency Pareto Frontier

- Why We Need to Solve the Privacy-Transparency Trade-Off

- Research is Constrained by Information Flows

- Healthy Market Competition for Information Services

- Data, Energy & the Environment

- Feedback Mechanisms & Information Flows

- Democracy & Public Health Conversation

- New Market Incentives

- Safe Data Networks for Business, Governance and R&D

- Conflict, Political Science & Information Flows

- Disinformation & Information Flows

- Conclusion

I started taking The Private AI Series by OpenMined

The series contains four courses, all are free. At the time of writing, only the first one is online.

- Our Privacy Opportunity

- Foundations of Private Computation

- Federated Learning Across Enterprises

- Federated Learning on Mobile

The first course is non-technical and contains about 8 hours of video, taught by Emma Bluemke and Andrew Trask. Additionally, they interview many experts. The course aims to provide an overview of what privacy means, where it currently fails, and how possible solutions look like. One key point is that there are new privacy-enhancing technologies on the rise that will change the way how humans collaborate. This brings with it many career and business opportunities.

If you’re interested, sign up at courses.openmined.org!

Lesson 1 is just introductory. This is my summary of Lesson 2 of Our Privacy Opportunity. In addition, I can recommend Nahua Kang's great summary, it is more thouroughly structured than mine, which I primarily wrote for my forgetful self.

Society Runs on Information Flows

The main topic of the course is the privacy-transparency trade-off and how it affects a huge number of issues. This lesson walks through some of the most important challenges to society and identifies how the privacy-transparency trade-off underpins them. Improving information flows, by solving this trade-off, can help us in many areas like disinformation, scientific innovation, and even democracy itself.

Information Flow

What is an information flow? Let's take the simple example of email. A sender, a message, a receiver. Probably one of the most straight-forward information flows. But even email is much more nuanced than just the three attributes sender, message, receiver:

- Should other people than the receiver be allowed to read it?

- Would I be comfortable with the receiver forwarding my email?

- The email provider could probably read it, do I trust them to not do so?

- Do I want the email provider to read my mail only for a specific purpose, like for spam detection, but not for targeted advertising?

- Am I sending my exact identity with the email? Anonymously? Or a mix: as a member of group?

- Do I know exactly who the recipient is? When I'm sending the mail to a doctor's office, who reads it?

- Can the receiver have confidence in the identity of the sender, whaf if my account was hacked?

Questions like these exist around every information flow.

Newly emerging communication channels: Snapchat deletes the messages once they've been read and prohibits forwarding or screenshotting. WhatsApp or Signal use end-to-end encryption for messages so it's impossible for anyone other than the intended recipient to read them. Users switch to these services because of seemingly tiny changes to the guarantees around information flow. This is the beginning of a revolution!

What Does Privacy Mean?

Privacy is not about secrecy. People feel that their privacy is violated if information flows in a way they didn't expect. It's all about the appropriate flow of information, not about the information itself.

Example: My face is considered public information as soon as I leave the house, because anybody can see it. So why is facial recognition software so troubling? Not only because it could be misused (i.e., for mass surveillance), but because it is identification without my consent. The information flow is not triggered by me, but by whatever system is watching me.

Data is Fire 🔥

There is the popular notion that "data is the new oil". A better analogy is "data is fire".

- It can be duplicated indefinitely

- It can help us prosper and solve problems

- It can cause irreparable damage if misused

This dual-use for good or harm is true for all kinds of data, not just data that is clearly sensitive like medical data.

Everything can be private data

Your grocery shopping list is boring, right? Not always. You might not care now whether somebody knows you're buying bread. But when you suddenly stop buying bread (and other carbs), it might be an indication of the diagnosis of diabetes. Suddenly it's very private information that you might not want to share.

And even when your exact identity is not recoverable, data can be used for targeting: As long as someone is able to reach you (via your browser, your church, your neighborhood, ...), your name is not at all necessary to do harm.

Example: Anonymization works so badly, that systematically exploiting its weaknesses can become a business model. Emma talks about a US company that buys anonymized health data and distributes "market insights" from it to insurance companies. They can then, for example, avoid selling insurance to high-risk communities like poor neighborhoods, where people are more likely to get sick.

Another example: Strava released an anonymized heatmap of user activities that revealed the location of US military bases. So, privacy can be relevant not only on an individual level but on an organizational or even national security level.

Strava released their global heatmap. 13 trillion GPS points from their users (turning off data sharing is an option). https://t.co/hA6jcxfBQI … It looks very pretty, but not amazing for Op-Sec. US Bases are clearly identifiable and mappable pic.twitter.com/rBgGnOzasq

— Nathan Ruser (@Nrg8000) January 27, 2018

Privacy and Transparency Dilemmas

Remember the dual-use of data 🔥 from the previous section. Due to the potentially harmful use of data, we have to constantly make trade-offs and decide whether to share information, weighing the benefits and the risks.

Stopping all information flow and locking all data is not the solution to the privacy issue. This would prevent good use of data (think medical care, climate research) and also make undesirable behaviour easier (money laundering, lack of accountability). Maximizing privacy could lead to a lack of transparency!

The Privacy-Transparency Pareto Frontier

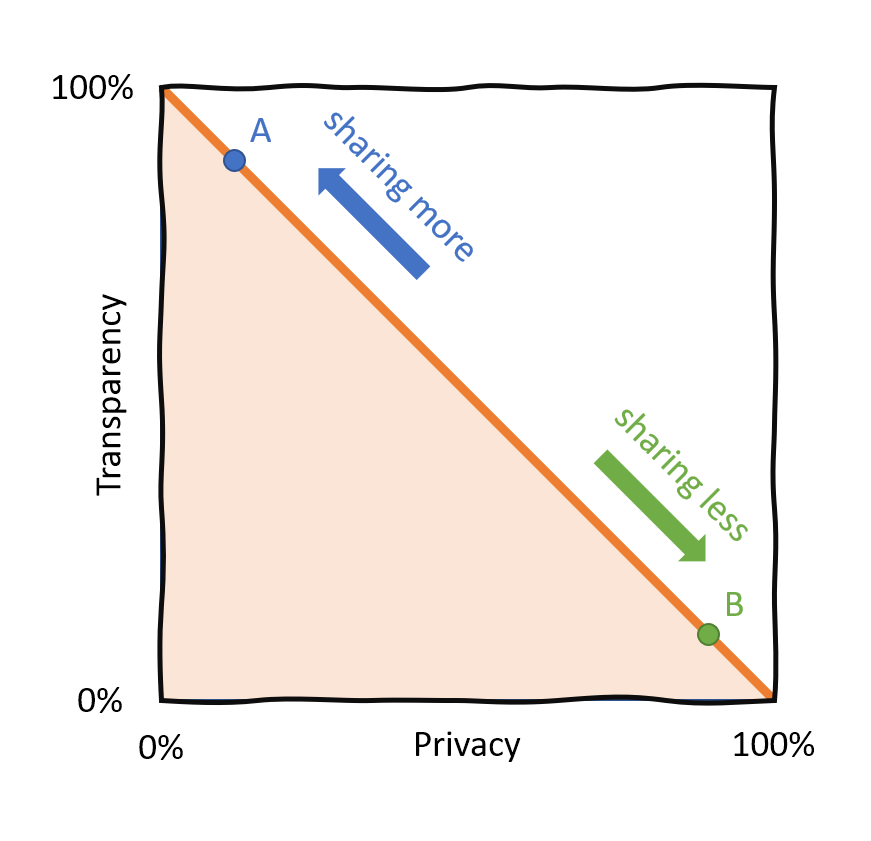

We used to have a classic Pareto trade-off between privacy and transparency. You had to decide whether you share information at the cost of privacy (point A in the chart). Or whether you keep information private, but at the cost of transparency (B). The question is: how can we move the frontier of this trade-off and have more of both at the same time?

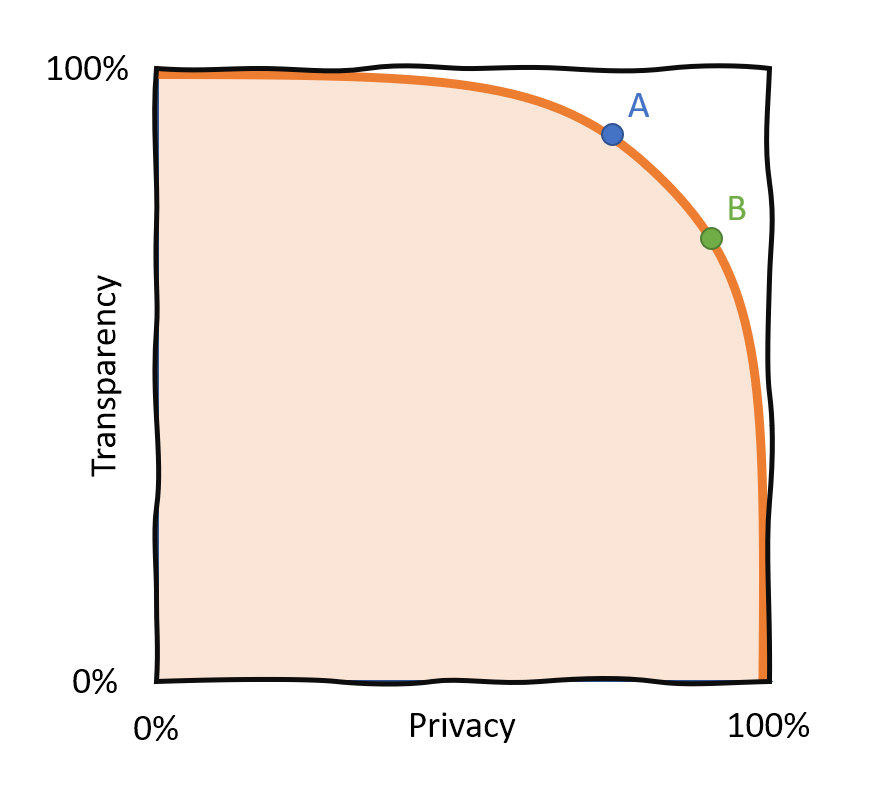

With new technologies, we can actually move the pareto frontier. Notice that point B in this chart has the same amount of privacy as in the first chart, but has a lot more transparency.

We don't have a zero-sum game anymore! This will affect every industry handling valuable, sensitive, or private data.

Thanks to these technologies, in the future governments won't have to choose between preserving the privacy of their citizens or protect national security, they can do both. Researchers won't have to decide whether or not to share their data, they can have the benefits from both. Corporations currently often have to choose between the privacy of their users and the accuracy of their products and services, in the future they can have both.

How these privacy-enhancing methods look like and which specific technologies are developed, will be covered later in the course.

Research is Constrained by Information Flows

If there was a way to share data across institutions while making sure it remained private and was used for good, all areas of research would benefit. More data would be available, it would be available faster, and also: experiments could be replicated more easily.

Healthy Market Competition for Information Services

Most services that handle your data will profit from locking you in. Because of privacy concerns they are inherently anti-competitive. More privacy restrictions can actually make it harder for new companies to compete (because you can't move your data from your old to the new provider).

We need more interoperability between information service providers.

EU citizens now have 7 rights over their data, including the right to be forgotten (a company has to delete all your personal data on request) and the right of access (on request, companies have to send you a copy of all data they have of you).

Data, Energy & the Environment

One of society's biggest challenges is the transition to green energy. The volatile nature of renewable energy sources makes nation-wide coordination of energy demand necessary.

An area where the privacy-transparency trade-off comes into play is smart meters. Smart meters are highly valuable for the transition to clean energy. Grid operators can have an accurate picture of energy demand, consumers can reduce energy waste. But smart meters can also be extremely privacy invasive, because one can build rich patterns of your energy data. How your daily habits are, when you are or are not at home etc.

Example: In Taiwan many people have air boxes in their homes to measure pollution. There was a community-driven effort to collect these measurements. They were able to coordinate with millions of people to get this data-sharing system working. The government didn't invest heavily in this technology, but was very interested in the data. In exchange they installed more air boxes in places like public parks and military zones.

Feedback Mechanisms & Information Flows

We often rely on the opinions of others when we make our decisions. Which car do you buy, which surgeon do you choose for a surgery? But there are more feedback mechanisms. Elections, protests, Facebook likes, going to prison, boycotting, gossip, are all feedback mechanisms.

What does a broken feedback scenario look like?

Examples:

- Medical care: When you go for surgery, how good is your surgeon? Can you ask for reviews of previous patients, could you talk to previous nurses? And even if you could, could you talk to enough patients or nurses?

- Consumer products: How do you know whether a product is any good? Amazon reviews are easy to fake, and the real ones come from only the most polarized users.

- Politics: A multiple choice question between a few candidates every 4 years is a terrible feedback system for reviewing the legislature of the past 4 years.

Most feedback information simply isn't collected, because it would be too personal to collect it.

Democracy & Public Health Conversation

Democracy is messy. Opinions are formed via social groups. In recent years there was an uptick in polarization, one of the reasons probably being social media where algorithms maximize engagement.

A better way can be found in Taiwan, with the Polis system. A community-built, nation-wide application that supports conversation between millions of users in Taiwan. It's not optimized for engagement, but for consensus. People can enter their opinions in written form (tweet-like), and a combination of NLP and voting clusters these opinions. Turns out, opinions aren't actually individual. There are less opinions than there are people because opinions are formed socially. However, the social groups that form our opinions aren't fixed but constantly changing.

So, some people emerge as being representative for specific opinions and become thought leaders for this particular matter. But now they must come up with a formulation that will get the most consent across opinions.

Example: When Uber wanted to come to Taiwan, people had very polarized opinions. The solution was: Uber was permitted a temporary license in Taiwan. During this time, the public Taxi sector should adopt the efficient algorithmic approaches from Uber while maintaining current labor standards. If they would succeed, Uber would be banned. If they failed, Uber would be banned unless they met the labor standards of the public system. That put just enough pressure on both sides, and in the end, the public system did improve so much that Uber was excluded.

New Market Incentives

Today's incentives of companies are often misaligned with the well-being of their users.

Example: Many online companies use attention (often called engagement) as their key metric. For some this intuitively makes sense, because their revenue is ad-driven. But even companies that run on a subscription model, like Netflix, do it. Netflix's former CEO Reed Hastings famously said they are competing with sleep ("And we’re winning!"). The question is: why?

One answer is that it's a readily available metric which is fine-grained and allows for optimization. Netflix's number of subscribers - which is the number they actually care about - is too coarse to use as a metric. Only if a movie was so good or so bad that it made users subscribe/unsubscribe, it would have a measurable effect.

Attention as a metric does work and is probably not a problem when used at a small scale. But at large scale and taken to the extremes it can cause harm, see the Netflix/sleep example.

Let's speculate about a better approach: Netflix could try to optimize their experience to improve the users' sleep. But how would they measure it and train an algorithm on it? Fitbits track sleeping patterns, but is it safe to share this data with Netflix? In general, these alternative metrics are called wellness metrics and can improve our lives.

Safe Data Networks for Business, Governance and R&D

How do privacy-transparency trade-offs affect important public information flows?

The European Commission recently proposed the Data Governance Act to improve data flows around the EU. The motivation: Businesses need data. And if they want to customize their product for each member state, they need data from these states. Data should flow easily through the EU. This increased access to data would advance scientific developments and innovations. This is especially important where coordinated action is necessary, like a global pandemic or tackling climate change.

So why should data not flow entirely freely?

- Commercially sensitive data like trade secrets should be protected. Data access can lead to theft of intellectual property.

- Data is valuable. Not just for a business, but for a country. Who controls the data has an impact on national security.

- Data can be private or sensitive. Fundamental rights of data protection have to be respected.

New threats to privacy: New mathematical tools allow reconstruction of personal details even from anonymized datasets. Free-flowing anonymized data access only seems like a good idea if you ignore all of the European history.

Technology advances faster than legislation. Regulation has to consider the power of future analysis techniques.

The privacy trade-off here is relevant to individuals, companies and countries. Companies and users should be able to trust that their data is used in a manner that respects their rights and interests. Trust will be crucial for data to be willingly shared.

But trust doesn't just arise. How can we protect the people's rights and interests?

Let's daydream: What if the data didn't have to move? What if the institutions within the home country had the only copy of a citizen's sensitive data, which the other countries accessed remotely and easily and in a controlled manner? Instead of transferring the data around Europe, out of the owner's control?

Today, there are new techniques to enable privacy-friendly analysis, including differential privacy which will be covered during this course.

Conflict, Political Science & Information Flows

One rational explanation of war: Mutual Optimism. It's extremely hard to predict the outcome of a battle, a war. Both sides can come up with an estimate that says, "we're more likely to win than not to win". The sum of the estimates is greater than 1. That's why nations go to war.

A way to share private military information to determine the winner (in a digital war game) ahead of time, but without actually giving away military secrets to the opponent, could potentially avoid wars.

This is true for other conflicts as well, like legal disputes or commercial competition. If the winner could be determined ahead some conflicts wouldn't be fought.

Moving the privacy-transparency trade-off is essential here as well.

Disinformation & Information Flows

The flow of news is one of the most important information flows in the world. How do you know that what you read in the news is actually true?

Before the invention of the printing press, people had the power to talk to maybe 50 people at the same time. For a story to be shared outside your own social circle, you would have to convince other people to talk about it. But today, where the average person has hundreds of contacts on social media, fake news and rumors can spread easily.

How to check if news is true?

- Have social media platforms emply people who check every bit that is published? Not feasible for hundreds of millions of users.

- Let a machine learning algorithm check whether a piece of news is true? Probably a bad idea in the long run, because news are an information bottleneck. Detecting fake news only by reading it doesn't work, you have to have knowledge of the world.

- Just get off social media? Maybe we're not supposed to be interconnected with that many people?

The most interesting solution is currently being deployed in Taiwan:

The Polis platform (developed by a hacker collective called g0v, pronounced "gov zero") aims to improve public discourse. Trained volunteers comment on suspicious stories with reliable sources one might check. Since these comments come from people you know from your local community, you already have a higher level of trust to them.

Another approach in Taiwan: using humor to foster trust between the state and its citizens. Humor over rumor!

🇹🇼 #Taiwan is combating #Coronavirus & managing the #COVID19 pandemic.

— Audrey Tang 唐鳳 (@audreyt) April 21, 2020

💡 Digital Social Innovation is key!

🚀 It’s fast, open, fair & fun.

🙌 Most importantly, it needs #AllHandsOnDeck.

🕔 Take 5 with me & get up to speed.

💻 Visit https://t.co/5D68ia7PcI & learn much more. pic.twitter.com/M5ecPnSPLF

Conclusion

The privacy-transparency trade-off or even privacy in general is in service of a higher aim: creating information flows within society that create social good.

I hope you found this summary helpful! Please let me know any feedback you have here in the comments or on Twitter, I'm @daflowjoe.

In Part 2 we will learn about the technical problems that cause the privacy-transparency trade-off.